The mountains of Utah held him at the end, as they had throughout his life whenever Hollywood became too much. Robert Redford died Tuesday morning at his home near Sundance, the remote Utah sanctuary he’d carved out decades ago as an antidote to the California dream machine. He was 89, and if there’s poetry in anything, it’s that he left this world in the one place he’d always insisted on being himself.

Redford’s death marks the passing of something larger than one man, no matter how famous. He was the last remaining connection to a specific moment in American cinema—those anarchic, possibility-drunk years between the studio system’s collapse and the blockbuster’s rise, when movies could still be political without being preachy, romantic without being saccharine, and commercially successful without abandoning their souls. He embodied that balance so completely that it looked easy, which may have been his greatest trick.

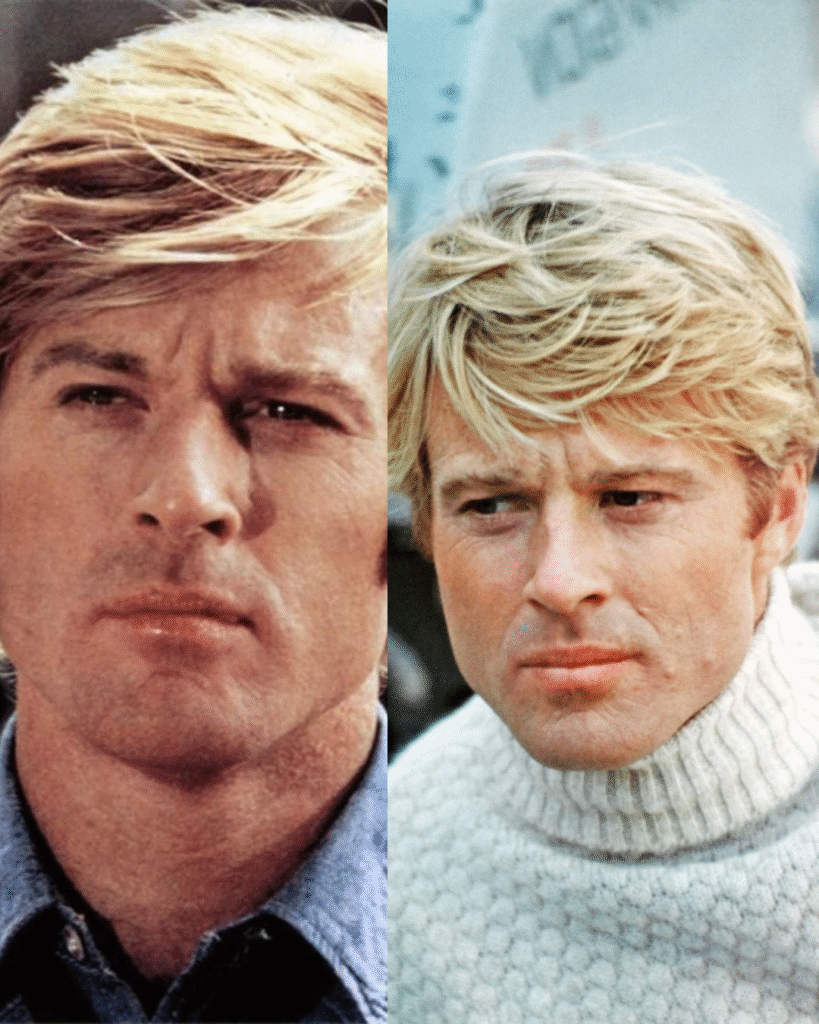

Consider the image most people carry of him: that shock of golden hair catching the light, those blue eyes suggesting depths he’d never quite let you reach, that smile hinting at secrets he’d never tell. He was beautiful in a way that should have been superficial but somehow wasn’t. There was intelligence behind the looks, conscience behind the charm. He made idealism sexy, which in the cynical 1970s was no small achievement.

The stardom arrived suddenly but not accidentally. By 1969, Redford had spent a decade learning his craft—Broadway stages, television guest spots, supporting roles that taught him how cameras worked and what they wanted from a face like his. Then George Roy Hill cast him opposite Paul Newman in “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” and everything changed. The chemistry between the two men was electric, their banter effortless, their timing immaculate. Audiences didn’t just watch them; they wanted to be them, or at least be their friend.

What followed was one of those rare stretches where an actor can seemingly do no wrong. “Jeremiah Johnson” turned him into a rugged icon of masculine self-reliance. “The Way We Were” proved he could break hearts as easily as win them. “The Sting” reunited him with Newman for a jazz-age caper so stylish it made larceny look like art. And “The Great Gatsby” cast him as Fitzgerald’s dreamer, a role that seemed almost too perfect—the golden boy playing the ultimate golden boy.

But Redford was shrewder than the roles suggested. While other stars of his generation chased ever-bigger paychecks or descended into self-parody, he began using his power for something else. “All the President’s Men” wasn’t just another thriller; it was a statement about journalism’s role in democracy, about the painstaking work of uncovering truth. Redford didn’t just star as Bob Woodward—he’d bought the film rights, hired the screenwriter, shepherded the project through development. He understood that movie stars could be producers, that fame was leverage, that the system could be bent toward better purposes if you knew where to push.

The 1980s brought a pivot that surprised many but shouldn’t have. “Ordinary People,” his directorial debut, was the opposite of everything his star persona suggested—intimate where he was larger-than-life, emotionally raw where he was controlled, focused on a fractured suburban family rather than heroic individuals. The Academy gave it Best Picture and Best Director, validating Redford’s instinct that he had more to offer than his face.

Yet even as he directed films throughout the next four decades—some celebrated like “A River Runs Through It,” others quickly forgotten—his most significant creative act was happening off-screen. In 1981, in those same Utah mountains where he’d eventually die, Redford founded the Sundance Institute with a simple mission: give voice to filmmakers the system ignored.

What he built became more than a festival. Sundance evolved into an institution that fundamentally altered American cinema’s ecosystem. Before Sundance, “independent film” was a marginal category, the domain of obsessives and outcasts. After Sundance, it was an industry, a aesthetic, a legitimate career path. Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, Paul Thomas Anderson, the Coen Brothers—their rise coincided with Sundance’s ascendance, and while correlation isn’t causation, Redford had created the conditions for their success.

The skeptics asked why someone who’d conquered Hollywood would work so hard to undermine it. But that was the point. Redford had never entirely trusted the system that made him rich and famous. He’d seen how it crushed unconventional voices, how it favored formula over imagination, how it measured worth in opening weekends rather than lasting value. Sundance was his answer—not revolution so much as alternative, a place where the industry’s rejects could become its future.

His later years brought the inevitable diminishment of age but also a kind of grace. He appeared less frequently on screen, choosing roles with greater care. “All Is Lost” in 2013 was a marvel of minimalism—Redford alone on a damaged boat, dialogue sparse, the performance purely physical. Critics marveled that a man in his late seventies could carry a film through sheer presence. Of course he could. He’d been doing it for fifty years.

His final performance came in “The Old Man & the Gun,” playing a gentleman bank robber who couldn’t stop even as age caught up with him. The parallels to Redford’s own career were obvious and probably intentional—an artist who’d spent decades getting away with things, charming his way through obstacles, staying one step ahead of whatever wanted to pin him down. The film ended with his character smiling at the possibility of one more job. Redford, having announced his retirement, smiled at the possibility of finally being done.

He wasn’t always easy. Colleagues occasionally found him remote, guarded in ways that suggested old wounds never entirely healed. He’d lost two sons—Scott to sudden infant death syndrome in 1959, James to cancer in 2020—tragedies that would have shattered anyone. Perhaps that’s where the guardedness came from, the sense that there were rooms inside him no one would ever enter. Or perhaps that was simply who he was: a private man in a public profession, protecting something essential from an industry that devoured everything it touched.

What remains is impossible to quantify but easy to feel. There’s the filmography, of course—dozens of performances, several fine films as a director. There’s Sundance, which will outlive everyone reading this. But there’s also something harder to measure: the example he set of how to be famous without being consumed by fame, successful without being corrupted by success, powerful without wielding that power cruelly.

In an industry of big personalities and bigger egos, Redford somehow managed to be substantial without being loud about it. He proved you could be a movie star and still care about things beyond yourself. He showed that commerce and art need not be enemies, that popular entertainment could carry weight, that beauty and brains weren’t mutually exclusive.

The last photographs show a man who’d aged into something finer than youth—weathered, white-haired, but unmistakably himself. The mountains held him at the end, just as they’d held him throughout those years when Hollywood wanted too much and he needed to remember who he’d been before the cameras found him.

Robert Redford leaves behind a wife, two daughters, countless admirers, and an industry he helped reshape into something slightly better than it might have been without him. In the end, perhaps that’s the most we can ask: that we leave things marginally improved, that we use whatever gifts we’re given to open doors for others, that we stay true to something beyond ourselves even when compromise would be easier.

The golden boy grew into a white-haired statesman who never entirely stopped being a rebel. And somewhere in the Utah mountains, as snow falls on empty trails and pine trees stand silent witness, a certain kind of Hollywood—principled, purposeful, possible—passed with him.